Learning from Bus Buddhists

In psychological terms, context is almost everything. Much as we like to think that we know how we will act and react in a given situation, without the richness of...

Why Women Take So Long to Choose and Men Jump to Conclusions

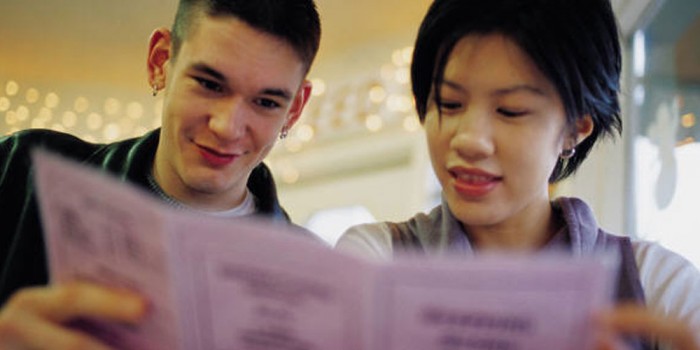

Let’s face it, most of us are familiar with the situation. The couple sit in the restaurant chatting happily, smiling at each other and enjoying themselves.

Then…

The menu arrives.

He glances at it, selects something and puts the menu down, suddenly remembering how hungry he is and hoping that the food will arrive very soon.

She sits back and starts looking at the menu as you might a favourite novel. She studies it with the sort of attention normally reserved for forensic investigations.

He tells himself to relax. “Don’t spoil the evening by getting cross,” he thinks to himself.

She is oblivious to his building discomfort. Wrapped up in the vast selection of delicious alternatives present. “Hmmm,” she wonders, “what would be best?”

Several minutes pass.

He can’t conceive what mental algorithms she’s juggling with that might necessitate such a long time between seeing the menu and choosing some food. He’s getting hungrier too.

Eventually, she looks up from the menu and asks in all innocence, “What are you having?” and for a fleeting moment he thinks about sticking a fork through his own hand to conceal his anger.

He tells her. “Oh, I was going to have that too, but if you’re having it I’ll go for this one.” Inside he’s shaking his head, “Why not choose what you want,” he thinks to himself.

So what’s going on in this scenario and why is it that there seems to exist such a large disparity between how men and women handle choices like these.

As a consumer behaviour expert, it’s a question I get asked a lot. And, until now, I’ve not read anything that has given me clues about why such a difference might exist, but I’ve observed enough occasions to be pretty certain there is a difference.

A recently published study is the first I’ve seen that helps me provide an answer.

First off we need to consider the issue of choice. As I explained in my recent article “Too Much Choice” choice is very much a mixed blessing. It feels like it’s a nice thing to have, but when presented with a large choice people are less likely to buy, and if they do buy likely to feel less satisfied with what they have bought.

Choice is confusing. Stressful.

The unconscious mind doesn’t like to feel confused (the theory of cognitive dissonance). It seeks to find a quick answer, typically by leveraging our capacity to see what we want to see in a situation (confirmation bias).

So what we do unconsciously is look for one small piece of evidence that fits with what we’ve experienced before and come to believe as true and ignore whatever else is going on that might conflict with this.

This may seem like a fairly dodgy way of going about life, mostly because it is likely to lead to us making all sorts of bad “decisions”. But it has the practical benefit, in evolutionary terms, of making us quick to act and, given how far we’ve got as a species, it seems to do us more good than harm.

Recently published research has found a difference in the way men and women handle stressful situations. Researchers wanted to investigate whether stress caused different levels of risk-taking in men and women.

They gave participants a task of inflating a virtual balloon. Each time a button was pushed to increase the size of the balloon the dollar payment they received increased. But participants knew that at some point between the balloon’s starting size and it filling the screen it would burst, at which point they would receive nothing.

The more you press the button, the more money you make, but the more likely it is that the balloon will burst.

Half the sample were put under stress – their hands were immersed in freezing cold water – to gauge if the physiological affect changed how much of a risk they would take with the balloon inflation game.

The results showed that both sexes behaviour did change under stress. Men took greater risks when they were stressed, women took fewer risks.

So it seems likely to me that the restaurant menu experience most of us have had is an example of similar forces at play.

As a man, my way of dealing with the stress of a wide choice is to take a chance, dive in on something that I expect will be OK, even if it means missing out on something else on the menu that, were it to be listed as a choice of just three or four dishes, I would probably realise I would prefer.

Whereas the female response is to take more time, ‘tend and befriend’, ask what other people are going to have so that a satisfactory choice is made in the broader social context.

It’s ironic that both sexes run the significant risk of choosing something other than the dish they would most like, were the situation not to be so stressful as a result of the large choice.

On the other hand, our capacity for confirmation bias will often mean we only choose to see the positive in what we’ve selected.

Source:Lighthall NR,Mather M,Gorlick MA,2009Acute Stress Increases Sex Differences in Risk Seeking in the Balloon Analogue Risk Task.PLoS ONE4(7):e6002.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006002